Tiny wars still don't work

By Tom Engelhardt

In terms of pure projectable power, there's never been anything like it. Its military has divided the world - the whole planet - into six "commands." Its fleet, with 11 aircraft carrier battle groups, rules the seas and has done so largely unchallenged for almost seven decades.

Its Air Force has ruled the global skies, and despite being almost continuously in action for years, hasn't faced an enemy plane since 1991 or been seriously challenged anywhere since the early 1970s.

Its fleet of drone aircraft has proven itself capable of targeting and killing suspected enemies in the backlands of the planet from Afghanistan and Pakistan to Yemen and Somalia with little regard for national boundaries, and none at all for the possibility of being shot down. It funds and trains proxy armies on several continents and has complex aid and training relationships with militaries across the planet.

Afghanistan and Pakistan to Yemen and Somalia with little regard for national boundaries, and none at all for the possibility of being shot down. It funds and trains proxy armies on several continents and has complex aid and training relationships with militaries across the planet.

On hundreds of bases, some tiny and others the size of American towns, its soldiers garrison the globe from Italy to Australia, Honduras to Afghanistan, and on islands from Okinawa in the Pacific Ocean to Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean. Its weapons makers are the most advanced on Earth and dominate the global arms market. Its nuclear weaponry in silos, on bombers, and on its fleet of submarines would be capable of destroying several planets the size of Earth. Its system of spy satellites is unsurpassed and unchallenged.

Its intelligence services can listen in on the phone calls or read the emails of almost anyone in the world from top foreign leaders to obscure insurgents. The CIA and its expanding paramilitary forces are capable of kidnapping people of interest just about anywhere from rural Macedonia to the streets of Rome and Tripoli. For its many prisoners, it has set up (and dismantled) secret jails across the planet and on its naval vessels. It spends more on its military than the next most powerful 13 states combined. Add in the spending for its full national security state and it towers over any conceivable group of other nations.

In terms of advanced and unchallenged military power, there has been nothing like the US armed forces since the Mongols swept across Eurasia. No wonder American presidents now regularly use phrases like "the finest fighting force the world has ever known" to describe it. By the logic of the situation, the planet should be a pushover for it. Lesser nations with far lesser forces have, in the past, controlled vast territories. And despite much discussion of American decline and the waning of its power in a "multi-polar" world, its ability to pulverize and destroy, kill and maim, blow up and kick down has only grown in this new century.

No other nation's military comes within a country mile of it. None has more than a handful of foreign bases. None has more than two aircraft carrier battle groups. No potential enemy has such a fleet of robotic planes. None has more than 60,000 special operations forces. Country by country, it's a hands-down no-contest. The Russian (once "Red") army is a shadow of its former self. The Europeans have not rearmed significantly. Japan's "self-defense" forces are powerful and slowly growing, but under the US nuclear "umbrella." Although China, regularly identified as the next rising imperial state, is involved in a much-ballyhooed military build-up, with its one aircraft carrier (a retread from the days of the Soviet Union), it still remains only a regional power.

Despite this stunning global power equation, for more than a decade we have been given a lesson in what a military, no matter how overwhelming, can and (mostly) can't do in the twenty-first century, in what a military, no matter how staggeringly advanced, does and (mostly) does not translate into on the current version of planet Earth.

A destabilization machine

Let's start with what the US can do. On this, the recent record is clear: it can destroy and destabilize. In fact, wherever US military power has been applied in recent years, if there has been any lasting effect at all, it has been to destabilize whole regions.

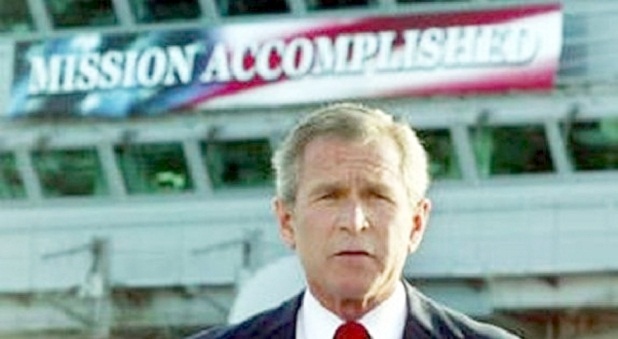

Back in 2004, almost a year and a half after American troops had rolled into a Baghdad looted and in flames, Amr Mussa, the head of the Arab League, commented ominously, "The gates of hell are open in Iraq." Although for the Bush administration, the situation in that country was already devolving, to the extent that anyone paid attention to Mussa's description, it seemed over the top, even outrageous, as applied to American-occupied Iraq. Today, with the latest scientific estimate of invasion- and war-caused Iraqi deaths at a staggering 461,000, thousands more a year still dying there, and with Syria in flames, it seems something of an understatement.

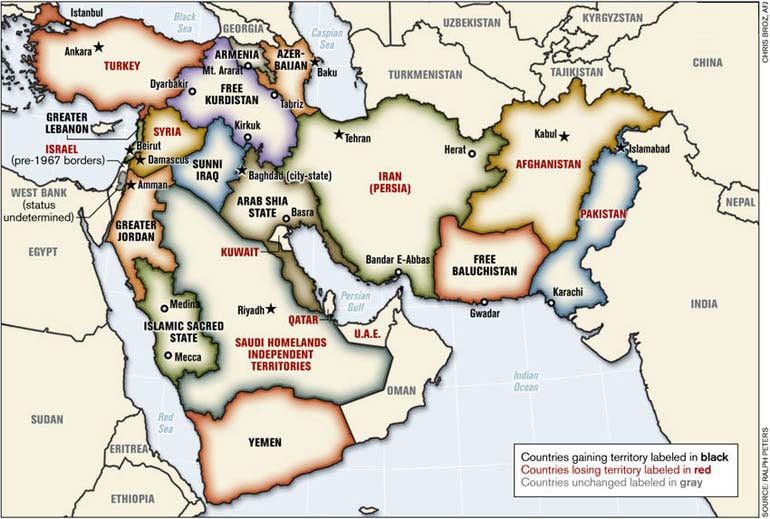

It's now clear that George W Bush and his top officials, fervent fundamentalists when it came to the power of US military to alter, control, and dominate the Greater Middle East (and possibly the planet), did launch the radical transformation of the region. Their invasion of Iraq punched a hole through the heart of the Middle East, sparking a Sunni-Shi'ite civil war that has now spread catastrophically to Syria, taking more than 100,000 lives there. They helped turn the region into a churning sea of refugees, gave life and meaning to a previously nonexistent al-Qaeda in Iraq (and now a Syrian version of the same), and left the country drifting in a sea of roadside bombs and suicide bombers, and threatened, like other countries in the region, with the possibility of splitting apart.

And that's just a thumbnail sketch. It doesn't matter whether you're talking about destabilization in Afghanistan, where US troops have been on the ground for almost 12 years and counting; Pakistan, where a CIA-run drone air campaign in its tribal borderlands has gone on for years as the country grew ever shakier and more violent; Yemen (ditto), as an outfit called al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula grew ever stronger; or Somalia, where Washington repeatedly backed proxy armies it had trained and financed, and supported outside incursions as an already destabilized country came apart at the seams and the influence of al-Shabab, an increasingly radical and violent insurgent Islamic group, began to seep across regional borders. The results have always been the same: destabilization.

Consider Libya where, no longer enamored with boots-on-the-ground interventions, President Obama sent in the Air Force and the drones in 2011 in a bloodless intervention (unless, of course, you were on the ground) that helped topple Muammar Gaddafi, the local autocrat and his secret-police-and-prisons regime, and launched a vigorous young democracy ... oh, wait a moment, not quite. In fact, the result, which, unbelievably enough, came as a surprise to Washington, was an increasingly damaged country with a desperately weak central government, a territory controlled by a range of militias - some Islamic extremist in nature - an insurgency and war across the border in neighboring Mali (thanks to an influx of weaponry looted from Gaddafi's vast arsenals), a dead American ambassador, a country almost incapable of exporting its oil, and so on.

Libya was, in fact, so thoroughly destabilized, so lacking in central authority that Washington recently felt free to dispatch US Special Operations forces onto the streets of its capital in broad daylight in an operation to snatch up a long-sought terrorist suspect, an act which was as "successful" as the toppling of the Gaddafi regime and, in a similar manner, further destabilized a government that Washington still theoretically backed. (Almost immediately afterward, the prime minister found himself briefly kidnapped by a militia unit as part of what might have been a coup attempt.)

Wonders of the modern world

If the overwhelming military power at the command of Washington can destabilize whole regions of the planet, what, then, can't such military power do? On this, the record is no less clear and just as decisive. As every significant US military action of this new century has indicated, the application of military force, no matter in what form, has proven incapable of achieving even Washington's most minimal goals of the moment.

Consider this one of the wonders of the modern world: pile up the military technology, pour money into your armed forces, outpace the rest of the world, and none of it adds up to a pile of beans when it comes to making that world act as you wish. Yes, in Iraq, to take an example, Saddam Hussein's regime was quickly "decapitated," thanks to an overwhelming display of power and muscle by the invading Americans. His state bureaucracy was dismantled, his army dismissed, an occupying authority established backed by foreign troops, soon ensconced on huge multi-billion-dollar military bases meant to be garrisoned for generations, and a suitably "friendly" local government installed.

And that's where the Bush administration's dreams ended in the rubble created by a set of poorly armed minority insurgencies, terrorism, and a brutal ethnic/religious civil war. In the end, almost nine years after the invasion and despite the fact that the Obama administration and the Pentagon were eager to keep US troops stationed there in some capacity, a relatively weak central government refused, and they departed, the last representatives of the greatest power on the planet slipping away in the dead of night. Left behind among the ruins of historic ziggurats were the "ghost towns" and stripped or looted US bases that were to be our monuments in Iraq.

Today, under even more extraordinary circumstances, a similar process seems to be playing itself out in Afghanistan - another spectacle of our moment that should amaze us. After almost 12 years there, finding itself incapable of suppressing a minority insurgency, Washington is slowly withdrawing its combat troops, but wants to leave behind on the giant bases we've built perhaps 10,000 "trainers" for the Afghan military and some Special Operations forces to continue the hunt for al-Qaeda and other terror types.

For the planet's sole superpower, this, of all things, should be a slam dunk. At least the Iraqi government had a certain strength of its own (and the country's oil wealth to back it up). If there is a government on Earth that qualifies for the term "puppet," it should be the Afghan one of President Hamid Karzai. After all, at least 80% (and possibly 90%) of that government's expenses are covered by the US and its allies, and its security forces are considered incapable of carrying on the fight against the Taliban and other insurgent outfits without US support and aid. If Washington were to withdraw totally (including its financial support), it's hard to imagine that any successor to the Karzai government would last long.

How, then, to explain the fact that Karzai has refused to sign a future bilateral security pact long in the process of being hammered out? Instead, he recently denounced US actions in Afghanistan, as he had repeatedly done in the past, claimed that he simply would not ink the agreement, and began bargaining with US officials as if he were the leader of the planet's other superpower.

A frustrated Washington had to dispatch Secretary of State John Kerry on a sudden mission to Kabul for some top-level face-to-face negotiations. The result, a reported 24-hour marathon of talks and meetings, was hailed as a success: problem(s) solved. Oops, all but one. As it turned out, it was the very same one on which the continued US military presence in Iraq stumbled - Washington's demand for legal immunity from local law for its troops. In the end, Kerry flew out without an assured agreement.

Making sense of war in the 21st century

Whether the US military does or doesn't last a few more years in Afghanistan, the blunt fact is this: the president of one of the poorest and weakest countries on the planet, himself relatively powerless, is essentially dictating terms to Washington - and who's to say that, in the end, as in Iraq, US troops won't be forced to leave there as well?

Once again, military strength has not carried the day. Yet military power, advanced weaponry, force, and destruction as tools of policy, as ways to create a world in your own image or to your own taste, have worked plenty well in the past. Ask those Mongols, or the European imperial powers from Spain in the sixteenth century to Britain in the nineteenth century, which took their empires by force and successfully maintained them over long periods.

What planet are we now on? Why is it that military power, the mightiest imaginable, can't overcome, pacify, or simply destroy weak powers, less than impressive insurgency movements, or the ragged groups of (often tribal) peoples we label as "terrorists"? Why is such military power no longer transformative or even reasonably effective? Is it, to reach for an analogy, like antibiotics? If used for too long in too many situations, does a kind of immunity build up against it?

Let's be clear here: such a military remains a powerful potential instrument of destruction, death, and destabilization. For all we know - it's not something we've seen anything of in these years - it might also be a powerful instrument for genuine defense. But if recent history is any guide, what it clearly cannot be in the twenty-first century is a policymaking instrument, a means of altering the world to fit a scheme developed in Washington. The planet itself and people just about anywhere on it seem increasingly resistant in ways that take the military off the table as an effective superpower instrument of state.

Washington's military plans and tactics since 9/11 have been a spectacular train wreck. When you look back, counterinsurgency doctrine, resuscitated from the ashes of America's defeat in Vietnam, is once again on the scrap heap of history. (Who today even remembers its key organizing phrase - "clear, hold, and build" - which now looks like the punch line for some malign joke?) "Surges," once hailed as brilliant military strategy, have already disappeared into the mists. "Nation-building," once a term of tradecraft in Washington, is in the doghouse. "Boots on the ground," of which the US had enormous numbers and still has 51,000 in Afghanistan, are now a no-no. The American public is, everyone universally agrees, "exhausted" with war. Major American armies arriving to fight anywhere on the Eurasian continent in the foreseeable future? Don't count on it.

But lessons learned from the collapse of war policy? Don't count on that, either. It's clear enough that Washington still can't fully absorb what's happened. Its faith in war remains remarkably unbroken in a century in which military power has become the American political equivalent of a state religion. Our leaders are still high on the counter-terrorism wars of the future, even as they drown in their military efforts of the present. Their urge is still to rejigger and re-imagine what a deliverable military solution would be.

Now the message is: skip those boots en masse - in fact, cut down on their numbers in the age of the sequester - and go for the counter-terrorism package. No more spilling of (American) blood. Get the "bad guys," one or a few at a time, using the president's private army, the Special Operations forces, or his private air force, the CIA's drones. Build new bare bones micro-bases globally. Move those aircraft carrier battle groups off the coast of whatever country you want to intimidate.

It's clear we're entering a new period in terms of American war making. Call it the era of tiny wars, or micro-conflicts, especially in the tribal backlands of the planet.

So something is indeed changing in response to military failure, but what's not changing is Washington's preference for war as the option of choice, often of first resort. What's not changing is the thought that, if you can just get your strategy and tactics readjusted correctly, force will work. (Recently, Washington was only saved from plunging into another predictable military disaster in Syria by an offhand comment of Secretary of State John Kerry and the timely intervention of Russian President Vladimir Putin.)

What our leaders don't get is the most basic, practical fact of our moment: war simply doesn't work, not big, not micro - not for Washington. A superpower at war in the distant reaches of this planet is no longer a superpower ascendant but one with problems.

The US military may be a destabilization machine. It may be a blowback machine. What it's not is a policymaking or enforcement machine.

Tom Engelhardt, co-founder of the American Empire Project and author of The United States of Fear as well as a history of the Cold War, The End of Victory Culture

By Tom Engelhardt

In terms of pure projectable power, there's never been anything like it. Its military has divided the world - the whole planet - into six "commands." Its fleet, with 11 aircraft carrier battle groups, rules the seas and has done so largely unchallenged for almost seven decades.

Its Air Force has ruled the global skies, and despite being almost continuously in action for years, hasn't faced an enemy plane since 1991 or been seriously challenged anywhere since the early 1970s.

Its fleet of drone aircraft has proven itself capable of targeting and killing suspected enemies in the backlands of the planet from

Afghanistan and Pakistan to Yemen and Somalia with little regard for national boundaries, and none at all for the possibility of being shot down. It funds and trains proxy armies on several continents and has complex aid and training relationships with militaries across the planet.

Afghanistan and Pakistan to Yemen and Somalia with little regard for national boundaries, and none at all for the possibility of being shot down. It funds and trains proxy armies on several continents and has complex aid and training relationships with militaries across the planet. On hundreds of bases, some tiny and others the size of American towns, its soldiers garrison the globe from Italy to Australia, Honduras to Afghanistan, and on islands from Okinawa in the Pacific Ocean to Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean. Its weapons makers are the most advanced on Earth and dominate the global arms market. Its nuclear weaponry in silos, on bombers, and on its fleet of submarines would be capable of destroying several planets the size of Earth. Its system of spy satellites is unsurpassed and unchallenged.

Its intelligence services can listen in on the phone calls or read the emails of almost anyone in the world from top foreign leaders to obscure insurgents. The CIA and its expanding paramilitary forces are capable of kidnapping people of interest just about anywhere from rural Macedonia to the streets of Rome and Tripoli. For its many prisoners, it has set up (and dismantled) secret jails across the planet and on its naval vessels. It spends more on its military than the next most powerful 13 states combined. Add in the spending for its full national security state and it towers over any conceivable group of other nations.

In terms of advanced and unchallenged military power, there has been nothing like the US armed forces since the Mongols swept across Eurasia. No wonder American presidents now regularly use phrases like "the finest fighting force the world has ever known" to describe it. By the logic of the situation, the planet should be a pushover for it. Lesser nations with far lesser forces have, in the past, controlled vast territories. And despite much discussion of American decline and the waning of its power in a "multi-polar" world, its ability to pulverize and destroy, kill and maim, blow up and kick down has only grown in this new century.

No other nation's military comes within a country mile of it. None has more than a handful of foreign bases. None has more than two aircraft carrier battle groups. No potential enemy has such a fleet of robotic planes. None has more than 60,000 special operations forces. Country by country, it's a hands-down no-contest. The Russian (once "Red") army is a shadow of its former self. The Europeans have not rearmed significantly. Japan's "self-defense" forces are powerful and slowly growing, but under the US nuclear "umbrella." Although China, regularly identified as the next rising imperial state, is involved in a much-ballyhooed military build-up, with its one aircraft carrier (a retread from the days of the Soviet Union), it still remains only a regional power.

Despite this stunning global power equation, for more than a decade we have been given a lesson in what a military, no matter how overwhelming, can and (mostly) can't do in the twenty-first century, in what a military, no matter how staggeringly advanced, does and (mostly) does not translate into on the current version of planet Earth.

A destabilization machine

Let's start with what the US can do. On this, the recent record is clear: it can destroy and destabilize. In fact, wherever US military power has been applied in recent years, if there has been any lasting effect at all, it has been to destabilize whole regions.

Back in 2004, almost a year and a half after American troops had rolled into a Baghdad looted and in flames, Amr Mussa, the head of the Arab League, commented ominously, "The gates of hell are open in Iraq." Although for the Bush administration, the situation in that country was already devolving, to the extent that anyone paid attention to Mussa's description, it seemed over the top, even outrageous, as applied to American-occupied Iraq. Today, with the latest scientific estimate of invasion- and war-caused Iraqi deaths at a staggering 461,000, thousands more a year still dying there, and with Syria in flames, it seems something of an understatement.

It's now clear that George W Bush and his top officials, fervent fundamentalists when it came to the power of US military to alter, control, and dominate the Greater Middle East (and possibly the planet), did launch the radical transformation of the region. Their invasion of Iraq punched a hole through the heart of the Middle East, sparking a Sunni-Shi'ite civil war that has now spread catastrophically to Syria, taking more than 100,000 lives there. They helped turn the region into a churning sea of refugees, gave life and meaning to a previously nonexistent al-Qaeda in Iraq (and now a Syrian version of the same), and left the country drifting in a sea of roadside bombs and suicide bombers, and threatened, like other countries in the region, with the possibility of splitting apart.

And that's just a thumbnail sketch. It doesn't matter whether you're talking about destabilization in Afghanistan, where US troops have been on the ground for almost 12 years and counting; Pakistan, where a CIA-run drone air campaign in its tribal borderlands has gone on for years as the country grew ever shakier and more violent; Yemen (ditto), as an outfit called al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula grew ever stronger; or Somalia, where Washington repeatedly backed proxy armies it had trained and financed, and supported outside incursions as an already destabilized country came apart at the seams and the influence of al-Shabab, an increasingly radical and violent insurgent Islamic group, began to seep across regional borders. The results have always been the same: destabilization.

Consider Libya where, no longer enamored with boots-on-the-ground interventions, President Obama sent in the Air Force and the drones in 2011 in a bloodless intervention (unless, of course, you were on the ground) that helped topple Muammar Gaddafi, the local autocrat and his secret-police-and-prisons regime, and launched a vigorous young democracy ... oh, wait a moment, not quite. In fact, the result, which, unbelievably enough, came as a surprise to Washington, was an increasingly damaged country with a desperately weak central government, a territory controlled by a range of militias - some Islamic extremist in nature - an insurgency and war across the border in neighboring Mali (thanks to an influx of weaponry looted from Gaddafi's vast arsenals), a dead American ambassador, a country almost incapable of exporting its oil, and so on.

Libya was, in fact, so thoroughly destabilized, so lacking in central authority that Washington recently felt free to dispatch US Special Operations forces onto the streets of its capital in broad daylight in an operation to snatch up a long-sought terrorist suspect, an act which was as "successful" as the toppling of the Gaddafi regime and, in a similar manner, further destabilized a government that Washington still theoretically backed. (Almost immediately afterward, the prime minister found himself briefly kidnapped by a militia unit as part of what might have been a coup attempt.)

Wonders of the modern world

If the overwhelming military power at the command of Washington can destabilize whole regions of the planet, what, then, can't such military power do? On this, the record is no less clear and just as decisive. As every significant US military action of this new century has indicated, the application of military force, no matter in what form, has proven incapable of achieving even Washington's most minimal goals of the moment.

Consider this one of the wonders of the modern world: pile up the military technology, pour money into your armed forces, outpace the rest of the world, and none of it adds up to a pile of beans when it comes to making that world act as you wish. Yes, in Iraq, to take an example, Saddam Hussein's regime was quickly "decapitated," thanks to an overwhelming display of power and muscle by the invading Americans. His state bureaucracy was dismantled, his army dismissed, an occupying authority established backed by foreign troops, soon ensconced on huge multi-billion-dollar military bases meant to be garrisoned for generations, and a suitably "friendly" local government installed.

And that's where the Bush administration's dreams ended in the rubble created by a set of poorly armed minority insurgencies, terrorism, and a brutal ethnic/religious civil war. In the end, almost nine years after the invasion and despite the fact that the Obama administration and the Pentagon were eager to keep US troops stationed there in some capacity, a relatively weak central government refused, and they departed, the last representatives of the greatest power on the planet slipping away in the dead of night. Left behind among the ruins of historic ziggurats were the "ghost towns" and stripped or looted US bases that were to be our monuments in Iraq.

Today, under even more extraordinary circumstances, a similar process seems to be playing itself out in Afghanistan - another spectacle of our moment that should amaze us. After almost 12 years there, finding itself incapable of suppressing a minority insurgency, Washington is slowly withdrawing its combat troops, but wants to leave behind on the giant bases we've built perhaps 10,000 "trainers" for the Afghan military and some Special Operations forces to continue the hunt for al-Qaeda and other terror types.

For the planet's sole superpower, this, of all things, should be a slam dunk. At least the Iraqi government had a certain strength of its own (and the country's oil wealth to back it up). If there is a government on Earth that qualifies for the term "puppet," it should be the Afghan one of President Hamid Karzai. After all, at least 80% (and possibly 90%) of that government's expenses are covered by the US and its allies, and its security forces are considered incapable of carrying on the fight against the Taliban and other insurgent outfits without US support and aid. If Washington were to withdraw totally (including its financial support), it's hard to imagine that any successor to the Karzai government would last long.

How, then, to explain the fact that Karzai has refused to sign a future bilateral security pact long in the process of being hammered out? Instead, he recently denounced US actions in Afghanistan, as he had repeatedly done in the past, claimed that he simply would not ink the agreement, and began bargaining with US officials as if he were the leader of the planet's other superpower.

A frustrated Washington had to dispatch Secretary of State John Kerry on a sudden mission to Kabul for some top-level face-to-face negotiations. The result, a reported 24-hour marathon of talks and meetings, was hailed as a success: problem(s) solved. Oops, all but one. As it turned out, it was the very same one on which the continued US military presence in Iraq stumbled - Washington's demand for legal immunity from local law for its troops. In the end, Kerry flew out without an assured agreement.

Making sense of war in the 21st century

Whether the US military does or doesn't last a few more years in Afghanistan, the blunt fact is this: the president of one of the poorest and weakest countries on the planet, himself relatively powerless, is essentially dictating terms to Washington - and who's to say that, in the end, as in Iraq, US troops won't be forced to leave there as well?

Once again, military strength has not carried the day. Yet military power, advanced weaponry, force, and destruction as tools of policy, as ways to create a world in your own image or to your own taste, have worked plenty well in the past. Ask those Mongols, or the European imperial powers from Spain in the sixteenth century to Britain in the nineteenth century, which took their empires by force and successfully maintained them over long periods.

What planet are we now on? Why is it that military power, the mightiest imaginable, can't overcome, pacify, or simply destroy weak powers, less than impressive insurgency movements, or the ragged groups of (often tribal) peoples we label as "terrorists"? Why is such military power no longer transformative or even reasonably effective? Is it, to reach for an analogy, like antibiotics? If used for too long in too many situations, does a kind of immunity build up against it?

Let's be clear here: such a military remains a powerful potential instrument of destruction, death, and destabilization. For all we know - it's not something we've seen anything of in these years - it might also be a powerful instrument for genuine defense. But if recent history is any guide, what it clearly cannot be in the twenty-first century is a policymaking instrument, a means of altering the world to fit a scheme developed in Washington. The planet itself and people just about anywhere on it seem increasingly resistant in ways that take the military off the table as an effective superpower instrument of state.

Washington's military plans and tactics since 9/11 have been a spectacular train wreck. When you look back, counterinsurgency doctrine, resuscitated from the ashes of America's defeat in Vietnam, is once again on the scrap heap of history. (Who today even remembers its key organizing phrase - "clear, hold, and build" - which now looks like the punch line for some malign joke?) "Surges," once hailed as brilliant military strategy, have already disappeared into the mists. "Nation-building," once a term of tradecraft in Washington, is in the doghouse. "Boots on the ground," of which the US had enormous numbers and still has 51,000 in Afghanistan, are now a no-no. The American public is, everyone universally agrees, "exhausted" with war. Major American armies arriving to fight anywhere on the Eurasian continent in the foreseeable future? Don't count on it.

But lessons learned from the collapse of war policy? Don't count on that, either. It's clear enough that Washington still can't fully absorb what's happened. Its faith in war remains remarkably unbroken in a century in which military power has become the American political equivalent of a state religion. Our leaders are still high on the counter-terrorism wars of the future, even as they drown in their military efforts of the present. Their urge is still to rejigger and re-imagine what a deliverable military solution would be.

Now the message is: skip those boots en masse - in fact, cut down on their numbers in the age of the sequester - and go for the counter-terrorism package. No more spilling of (American) blood. Get the "bad guys," one or a few at a time, using the president's private army, the Special Operations forces, or his private air force, the CIA's drones. Build new bare bones micro-bases globally. Move those aircraft carrier battle groups off the coast of whatever country you want to intimidate.

It's clear we're entering a new period in terms of American war making. Call it the era of tiny wars, or micro-conflicts, especially in the tribal backlands of the planet.

So something is indeed changing in response to military failure, but what's not changing is Washington's preference for war as the option of choice, often of first resort. What's not changing is the thought that, if you can just get your strategy and tactics readjusted correctly, force will work. (Recently, Washington was only saved from plunging into another predictable military disaster in Syria by an offhand comment of Secretary of State John Kerry and the timely intervention of Russian President Vladimir Putin.)

What our leaders don't get is the most basic, practical fact of our moment: war simply doesn't work, not big, not micro - not for Washington. A superpower at war in the distant reaches of this planet is no longer a superpower ascendant but one with problems.

The US military may be a destabilization machine. It may be a blowback machine. What it's not is a policymaking or enforcement machine.

Tom Engelhardt, co-founder of the American Empire Project and author of The United States of Fear as well as a history of the Cold War, The End of Victory Culture

)

)

Comment